On September 30, a historic marker was unveiled during a quiet ceremony held at the corner of Richardson and Humie Olive Roads in Apex. The reason is simple as a veritable field of dreams once stood there and from 1927 to 1977 this was the epicenter of fun, fellowship and faith for the Friendship community.

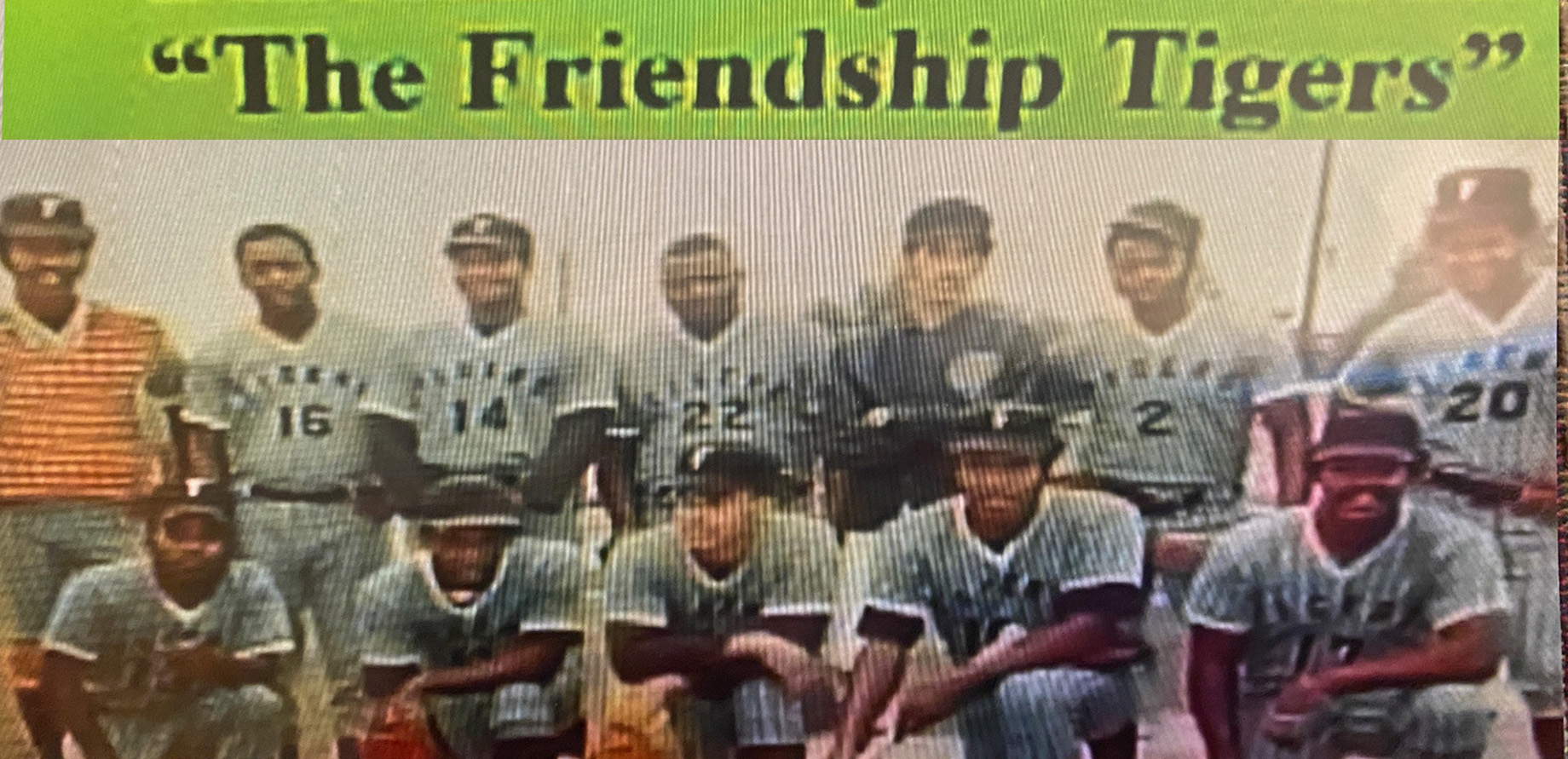

The marker, located on the site of home plate, sits in the shadows of newly constructed townhomes. It pays tribute to the field and the team and perhaps, most importantly, to those instrumental in starting and keeping the Friendship Tigers baseball team the only game in town for 50 years.

I spoke to Larry Harris who has lived in Friendship his entire life and about whom I have written before in these pages. He and eight passionate community members formed a committee and set out to erect the marker to ensure that this important historic site and the people who made it so are memorialized and celebrated.

The Tigers’ baseball field was a converted cornfield owned by Lattie and Bessie R. Scott, who also owned the general store and juke joint which sat directly across the street from the field. Larry’s father, Willie Harris, had an infectious love of baseball. “Mr. Willie,” as he was known around town, reached out to the Scotts since he knew the field was no longer being used to grow corn, and, true to form, the Scotts were happy to offer the cornfield to the team. The Scotts had a well-deserved and respected reputation in Friendship for their kindness and generosity and were affectionately called “Big Papa” and “Big Mama.”

The field, an undulating hodgepodge of grass, dirt, felled cornstalks, and rocks was beautiful in its uniqueness. Regardless of its condition, it gave the Tigers a place to practice and play. This was their home field. In addition, the general store and juke joint across the street were social gathering places for young people in Friendship. Kids would dance to the tunes emanating from the jukebox while the adults cheered on the Tigers across the street. Like bookends, the two most popular churches in the area flanked the field and the juke joint. Fun, fellowship and faith, indeed.

Mr. Willie and the Team

Willie Harris was an outstanding catcher and an accomplished hitter, but Larry made sure to underscore that his father’s impact transcended events on the field. In the end, it was Mr. Willie who was instrumental in organizing the Friendship team. As a player, coach, manager and recruiter, he ushered the team through its 50 years. Mr. Willie understood that the best place for young black men when they weren’t on the job was on the ball field. Playing baseball kept these men safe in often perilous times and taught them important life lessons.

The Tigers were part of the North Carolina Tobacco League which was a subset of the greater North Carolina Negro League. Although these were Negro leagues, players on the Friendship team reflected this integrated community with black, white and indigenous residents represented. Larry called it a true melting pot.

And, within this melting pot, a frequent rite of passage was being given a nickname. Some of the notable Tiger team nicknames included “Cool Cat,” Sylvester “Winckey” Gilbert, “Big Train” Cozart, “Rabbit” Thorpe and Lather “Piggley Wiggley” Harris.

The Tobacco League featured about 15 teams that were scattered across Wake, Durham, Chatham and Johnston Counties. Baseball season commenced on Easter Monday and extended through Labor Day. All games were played on Saturdays with the post-season schedule of playoff games sometimes falling on Sunday afternoons.

On game days, Mr. Willie led a caravan of Tiger players, coaches and fans in his pick-up truck with the others following behind. Children who were not yet ready to play were sometimes asked to be ball boys. Baseballs were expensive and with the field’s perimeter marked by cornfields and forest, ball boys saved time and money when foul balls, passed balls and home runs disappeared, albeit temporarily.

Balls weren’t the only equipment challenge the team faced, but, like any good team, they always rose to the challenge and found a way to carry on. The rule of thumb with all equipment was to preserve it and keep it usable for as long as possible.

Gloves weren’t always easy to come by so players would share gloves with the other team, baseball bats would be taped when they inevitably split or cracked, balls were reused for as long as possible, and despite the best efforts of the ball boys, losing balls to the elements was a fact of baseball life. Bases were created using what was available, with burlap sacks filled with pine straw being a frequent choice. Though formal uniforms were uncommon and cleats the same, everyone wore a baseball cap.

Game day was a community event with moms selling hot dogs and sodas under the shade trees in foul territory down the third base line. Any money made was used to purchase equipment and supplies for the team.

“The game of baseball was highly regarded in Friendship. All of the family could be involved. It was the center of the nucleus of the community by way of location. There were two historic black churches in the area. Yes, we farmed and worked hard from sun-up to sun-down But, on Saturday, it was game time. This was a wholesome activity for the whole family. Wives and children would come. They would bring food, chairs, and when we were on the road, they would travel with the team,” Larry said.

Because Mr. Willie did so much for this team, it seemed only right that he would get the chance to play against a baseball icon. That chance came in the 1950s when Hank Aaron came through Raleigh with a traveling team. Mr. Willie and a hand-picked team of players from the Tobacco League took them on at Chavis Park and Aaron even suited up and played. Mr. Willie’s team lost by one run. Even still, this was without a doubt the thrill of his lifetime.

For the 50 years these Friendship Tigers played, fathers and sons, uncles and nephews, brothers-in-arms teamed up. It was a family affair that spanned generations. But change was coming, as it always does. Employment, educational and military opportunities expanded. Integration replaced segregation. Society was changing.

In 1983, six years after the last league games were played at the Scotts’ old corn/baseball field, Mr. Willie Harris died.

“It was the end of an era,” Larry lamented.

After speaking to Larry for this story, we took a drive to the historic marker. Larry pointed out the location of dugouts, the first and third base lines, the juke joint, the spots where the moms set up their hot dog sales, and so on. We then drove down and around into the middle of the townhomes, which was centerfield back then. This place was unmistakably special to Larry.

“We won a lot of games and accumulated a lot of trophies. It’s funny because I wasn’t interested in baseball early on but with my dad’s love of the game, it was only a matter of time before I was hooked,” he said.

As Larry and I walked back to the car, I turned and looked back at the marker and thought, for a moment, that I heard someone yell, “Play ball!”

A life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives.

– Jackie Robinson