Apex Nature Park and the adjacent Seymour Athletic Fields are places that hustle and bustle with people always coming and going. Nestled just beyond the tennis courts is another spot that bustles with activity, but its visitors have wings.

Specifically, this is the park’s 1,400-square-foot pollinator garden and among its winged visitors are migrating monarch butterflies. The garden is among thousands of registered waystations with Monarch Watch, a national nonprofit dedicated to the research and conservation of these unique orange and black creatures.

“The Town of Apex is in the path of the annual eastern monarch migration and with monarch populations drastically decreasing, we want to do our part to help and provide a habitat for this beautiful species to eat and rest while on their big journey,” said Ellison Lambert, who manages community workdays at the garden as the town’s volunteer coordinator.

Like all butterflies, the monarch is a wisp of a creature. Small, delicate and weighing next to nothing. When it comes to monarchs, though, add the word mighty to that description. These beautiful butterflies travel 50 to 100 miles in a day and several thousand in total as part of their annual migration across North America.

The monarch migration is considered a natural wonder, and the eastern flight path includes North Carolina. Monarchs pass through the state in late summer/early fall and then again in mid-to-late spring. Migration timing can vary, but generally, late September is the peak time to see monarchs during their fall migration through the state.

Up to 100 million monarchs migrate annually according to estimates by Monarch Watch, which is based at the University of Kansas. Monarchs migrate further than any tropical butterfly and are the only butterfly to annually complete a two-way migration over such a great distance, according to the organization.

“Monarchs are pretty unique,” said Kristen Baum, director of Monarch Watch and a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the university. “We have other butterflies that migrate, but it’s a much shorter distance.”

Collectively, habitats along the monarch’s migratory routes are commonly called the “Butterfly Highway,” a conservation program of the North Carolina Wildlife Federation (NCWF). This state-wide conservation initiative, which began in 2016, aims to restore habitats lost to urbanization and create a network of native flowering plants to support monarchs and other pollinators.

With so many miles to fly, it’s no wonder travel-related concepts, phrases and actual roadways are associated with monarchs.

The National Wildlife Federation (NWF), for instance, works with state transportation departments from Texas to Minnesota to support its Monarch Highway habitat program along the Interstate 35 corridor, which corresponds with the butterflies’ central flyway.

And, in Illinois, the pollinator-friendly habitats of the Route 66 Monarch Flyway follow along the historic road’s scenic by-way from Chicago to St. Louis.

Begin Navigation, 3,000 Miles to Reach Your Destination

The monarch migration onramp starts in southern Canada and northern regions of the U.S. Monarchs spend their summer in these areas enjoying comfortable temperatures, but beginning in August environmental cues, such as day length and temperature change, trigger the need to head south. Monarchs can’t survive harsh winters, so by the millions they metaphorically pack up and hit the road, or rather, the skies.

Monarchs that follow the Western North American migration path overwinter along the California coast. Monarchs flying along the Eastern North American migration path head to mountains of central Mexico.

By November, the monarchs reach their overwintering destinations and it’s time to rest. They roost in trees, covering a single tree by the tens of thousands.

In early spring, vacation is over and it’s time to head home. During the spring migration monarchs will pass through N.C. again.

As the monarchs travel back, they mate and lay eggs along the way. The resulting butterflies, which are the first- and second-generation descendants of the overwintering monarchs, will reach their northern breeding grounds by summer.

Monarchs then breed throughout the summer, producing two to three more generations, until August comes and it’s time to begin the fall migration south again. The only exception to the annual migration is the monarchs that permanently live in Florida.

Monarchs make the long journey south in a single generation, meaning a single butterfly travels the entire way, which could be up to 3,000 miles, according to U.S. Forest Service (USFS) research.

Amazingly, these monarchs that have never migrated before instinctively travel the same path and roost in the same trees as the generations before them.

Exactly how this internal homing device works remains a mystery, but researchers suspect it may be a combination of the sun’s position and the magnetic pull of the earth, according to USFS.

Construction Ahead: Maintaining the Monarch Highway

For these migratory “road trips,” monarchs need habitats — places to stop for food, rest and to complete their life cycle. It takes a lot of energy to fly 50 to 100 miles per day, so monarchs seek out nectar-rich flowering plants. The nectar has the energy and nutrition they need to power up and refuel.

Habitats with milkweed are absolutely crucial for monarchs. Part of the monarch butterfly life cycle is the larvae (caterpillar) stage and milkweed is the sole food source for monarch caterpillars.

With the loss of natural habitat through urbanization, stops filled with nectar and milkweed are harder to find and monarch numbers have declined as a result.

The National Wildlife Federation (NWF) estimates the monarch population has dropped 90% since 1990, according to its website. The organization points to this as an indicator of habitat decline causing stress for monarchs and other pollinators in general.

“I would think of it as a ‘flagship species,’ as kind of being an ambassador for the larger community that uses that same type of habitat,” said Baum.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) notes on its website that the number of monarchs in overwintering sites has declined since communities and scientists began tracking them 20 years ago.

“This overwintering season was the second lowest on record,” Baum said and explained that this is determined by comparing measurements of the areas where the monarchs swarm in the trees each migration.

The status of the monarch population is an ongoing topic. In December 2020, the USFWS did not include the monarchs on its list of endangered species, stating it was “warranted but precluded” because of other higher priorities.

Instead, the USFWS encouraged ongoing monarch conservation efforts and stated it will continue to review the species’ potential listing each year. An updated decision is expected by December 2024.

Next Exit, North Carolina

Residents and communities can join conservation efforts by creating stops, a.k.a. habitats, along the highway. Together, these habitats not only help monarchs survive, but also other pollinators, such as bees and birds.

This is the exact thinking behind the pit stops of NCWF’s statewide Butterfly Highway program and the national waystation program by Monarch Watch.

“By protecting the monarch, you also protect other critical pollinators,” said Alden Picard, a conservation coordinator with NCWF, an affiliate of the NWF.

Picard noted that habitats of all sizes, whether in small planting containers or large public gardens, work together to help monarchs and other pollinators.

“What happens when everybody gets involved, is we start to glue back together and connect corridors of habitat with our pollinator pit stops,” he said.

“Like it says in the name, it gives them a highway, a corridor, areas to complete their life cycle, in an otherwise urbanized and fragmented landscape. So, it’s kind of like the glue. These pollinator pit stops are the glue for conservation. And it starts with one and it just builds and it snowballs.”

NCWF has over 3,400 registered Butterfly Highway pit stops across North Carolina, as well as some in neighboring states. Monarch Watch has more than 47,000 waystations nationwide and the Town of Apex’s pollinator garden is among them.

The garden, which was installed in 2022, is filled with milkweed, black-eyed Susan, goldenrod, aster varieties, obedient plant and other nectar-filled goodies pollinators love. It’s also part of the Town’s overall efforts to help monarch butterflies and other pollinators, such as bees. Lambert said the Town is continuing to develop the garden, including adding more plants and milkweed this fall.

Since 2020, Apex Mayor Jacques Gilbert has annually shown his support for the monarch by signing the Mayors’ Monarch Pledge, a program the NWF started in 2015.

More than 600 mayors and local community leaders across the country have taken the pledge, which involves committing to supportive practices, such as reducing or eliminating pesticides, restoring habitats and encouraging residents to do the same.

“The pledge does have some components to it,” said Gibert, “but one of the things I really like is how the pledge is saying, ‘Hey, I represent the Apex community and we’re serious about this and we’re going to support this initiative,’ but also encourage other people, other residents, our neighbors to consider planting their own garden and being a part of what we’re doing here.”

The pledge was first brought to Gilbert’s attention by students in Katie Thompson’s third grade class at Pine Springs Preparatory Academy in Holly Springs. Annually, her students write to leaders encouraging them to take the Mayors’ Monarch Pledge. Thompson, who teaches global education at the school, added the letter-writing activity to her pollinator lessons beginning in 2018.

“After learning about monarchs, specifically their migration, life cycle, and drastically decreasing numbers, the kids are so eager to help this endangered species,” said Thompson, who is also an officer and long-time member of the South Wake Conservationists, a local chapter of NCWF.

“Raising awareness and getting towns and cities on board by signing the Mayors’ Monarch Pledge is the best thing we can do from our classroom to make the biggest difference for monarchs.”

Overall, 17 mayors have accepted the students’ request, even in places as far as Georgia, Texas and Canada. The NWF is now sharing the program idea with teachers across the U.S.

When Gilbert re-signs the pledge each year, it’s part of an official proclamation that is presented to the students during a Town Council meeting.

“We need to publicly recognize this and, again, it’s another way to show our residents we are serious about this and to join in,” he said. “And, how rewarding for students to come into the council chambers and receive that [proclamation] from the mayor-council. We just really try to raise it up and say, ‘Thank you for what you have done to help our town in your unique way.’”

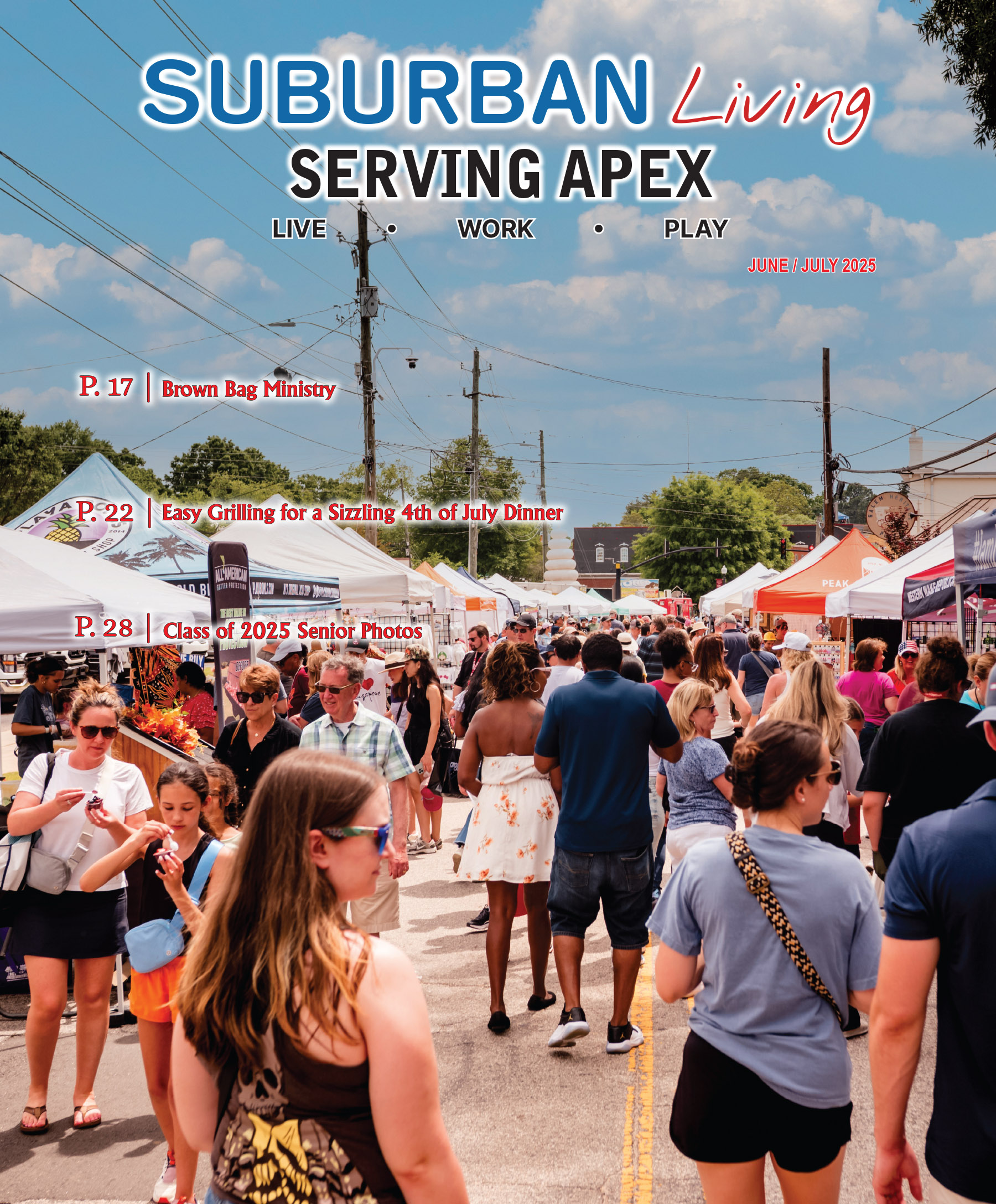

Anyone at the Apex EarthFest celebration in April may have seen the Pine Spring students at their Monarchs Matter booth. Gibert stopped by to see how the students were doing as they gave away free milkweed plants and seeds to anyone who pledged to plant them and stop using pesticides. The students gave away 66 plants and around 100 seed packets.

Gilbert noted that EarthFest, garden workdays and other programming not only helps the monarchs and pollinators, but also connects Apex residents.

“It’s moments like these that we can join in together, and do things together, like special events. And, also with this monarch pledge, ‘Hey, plant a pollinator garden and join in taking care of these monarch butterflies, and we can do it together.’ So, that is something I like putting out there.”

Baum also noted how monarchs connect people. “Monarchs are definitely unique for many aspects, the migration being one of those,” she said. “And they’re also a great connector of people.

“The number of different organizations and groups that have come together to support monarchs, and so many classrooms in K through 12 have included monarchs. So, it’s such a huge part of lots of people’s lives; they have monarch stories they remember.”

Join the Highway Crew

If you want to help monarchs by adding your own highway habitat filled with nectar and milkweed, here are some suggestions to get you started. Plus, ways to learn more about monarchs in general:

Check out the website for NCWF (ncwf.org) and Monarch Watch (monarchwatch.org) for tips and tools to create and register habitats that help monarchs along their journey.

Fill your garden with plants native to your area. Pollinators native to an area evolved alongside these plants and their life cycles work in tandem. For instance, plants blooming exactly when monarchs and other pollinators need nectar.

Plant a variety of brightly colored, nectar-rich flowering native plants that attract monarchs and other pollinators. Purple coneflower, black-eyed Susan, cardinal flower, garden phlox, and aster varieties are popular and easy-to-grow choices.

Have something blooming from spring through summer. Goldenrod is a nice addition to a garden since it blooms in the late summer and early fall after many other plants have stopped.

Plant native milkweed varieties, such as common milkweed, swamp milkweed and butterfly weed. Both common and swamp milkweeds spread by seed and rhizomes (runners), so those are best for larger gardens. Butterfly weed does not spread by rhizomes, so it works well in smaller gardens. It also does well in drier soils that get lots of sun. Milkweeds are also flowering nectar plants, which benefit additional pollinators.

Look for native milkweed at plant nurseries and plant sales, such as those at J. Raulston Arboretum in Raleigh. Through its Butterfly Highway program, NCWF offers seed packets for sale online that include two types of milkweed and a variety of native flowering plants. Monarch Watch has an online Milkweed Market for buying flats of plant plugs, including a free program for schools and habitat restoration sites.

Avoid planting tropical milkweed. Since tropical milkweed isn’t native to the U.S., it blooms at the wrong time and can disrupt the monarchs’ migration. It can also carry a harmful parasite.

Participate in Monarch Watch’s ongoing monarch tagging program, which is a large-scale community science project that aids research. Participants tag monarchs and release them, as well as record any tagged monarchs they encounter. Check the organization’s website for information about tagging kits and how to tag.

Sign up for the “Butterfly Highway Newsletter” by NCWF for a variety of helpful tips and interesting stories.

Track any monarch sighting with Journey North (www.journeynorth.org). Journey North, based at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Arboretum, is described as the largest citizen-based science program in North America. The program relies on everyday people to report monarch sightings, which become part of an online searchable map. Sightings include descriptions of monarch activity and photographs.