The Apex Union Depot is the most prominent site in Apex and has a long and varied history. Originally constructed in 1870, a new wooden depot was built in 1906, when a second set of tracks was laid for the Durham and Southern Railroads. By 1911, more than thirty trains passed through Apex daily carrying passengers and freight. This wooden depot was unsuitable for the citizens of Apex, as there were no restroom facilities and no heat in the depot. The Seaboard Railroad, however, blamed the town, as there was no sewer system or electricity in the town.

In 1911, fire destroyed most of the downtown business area, and although the railroad water tank was destroyed, the frame depot remained untouched. As a result of this fire, the town commissioners passed an ordinance “requiring all building within the downtown fire district be constructed of brick.” Today you will note that all the stores in the first and second blocks of North Salem Street are constructed of brick. After the fire, the town officials and the railroad started talking about replacing the depot. In late 1913 or early 1914, the depot once again caught fire. From this fire a serious movement started for the construction of a new depot which was built of brick and open for business by early 1915 for both passenger and freight. When completed, the depot cost $8,586.

A train depot made of brick for such a small town as Apex was almost unheard of in those days. It was considered an expensive ordeal. A brick-constructed depot was for such towns as Raleigh, not Apex. Of course, if the depot was to be built on the present site, the ordinance stated it must be built of brick. It seems that the railroad engineers were unhappy with the deal, so they built the freight depot just outside the fire district and it was built of wood.

The remarkably well-preserved depot is built on a simple rectangular plan, measuring 76’8” by 30’6”, with 13’6”-wide bays projecting five feet at the centers of the longer trackside and Salem Street elevations. A bell-cast hip roof covers the building and is still laid with the “Cartwright Victoria Galvanized Shingles or equal” specified in the architectural drawings. A seven-foot roof overhang shelters the walls, supported at the corners with heavy chamfered brackets. On the Salem Street side, the bay terminates under the slope of the roof, while the trackside bay breaks through the roof to form a hipped dormer.

The dark red brick veneer, laid with red tinted mortar, may be the “Oriental Brick” specified in original drawings. Windowsills, doorsills, and a continuous stringcourse around the building, which doubles as the sills of the larger windows, are brown sandstone. Several windows are original poured glass. The baggage room doors on the south end of the building provided access for baggage carts, and the double-leafed sliding doors at the rear of the room opened to the baggage loading dock. Original, conical cast-iron corner guards manufactured by Raleigh Iron Works protect all four exterior corners of the building and the jambs of the baggage room doors.

The interior plan has retained most of the 1914 design, which included racially segregated waiting rooms and rest rooms, an arrangement common to all depots built during the era. The waiting room for whites (north end) and blacks (south end) are divided across the center of the building by the stationmaster’s office, which extends into the trackside bay on the back of the building, and the utility closets and restrooms on the Salem Street side. The north side waiting room was partitioned on the north end to create a separate lounge and restrooms for white women. The restroom has been replaced with a storage area. On the south side, the black waiting room remains intact, but the baggage room has been partitioned for a small mechanical room. The stationmaster’s office remains much as originally configured. What were formerly restrooms for white and black men, serve as men’s and women’s today. A narrow hall connects the two former waiting rooms, and the previous black women’s restroom has been converted into a kitchen by the current occupants.

The interior finish is well preserved. Walls are plaster over a wainscot with a symmetrically molded 6 1/4” chair rail, a dado paneled with vertical beaded boards, and a wide baseboard. Windows and door frames, including those of the ticket windows, are molded and mitered. Three fireplaces, one double-sided, originally heated the two waiting rooms and the separate women’s lounge. The fireplaces’ elaborate paneled mantels of Neo-classical design have Ionic capitals on the pilasters flanking the fireplace openings and carry a deep shelf. One wooden stall with louvered doors remains in the restrooms and the oversize urinal in the men’s restroom is still functional. A heavy iron light fixture with six railroad lanterns hangs in the main lobby. The lanterns, now converted from oil to electric, are stamped with seals from five different railroads. Several switchmen’s lanterns hang outside the building, and a small metal plaque embedded in the rear of the building identifies the highest point on the railroad.

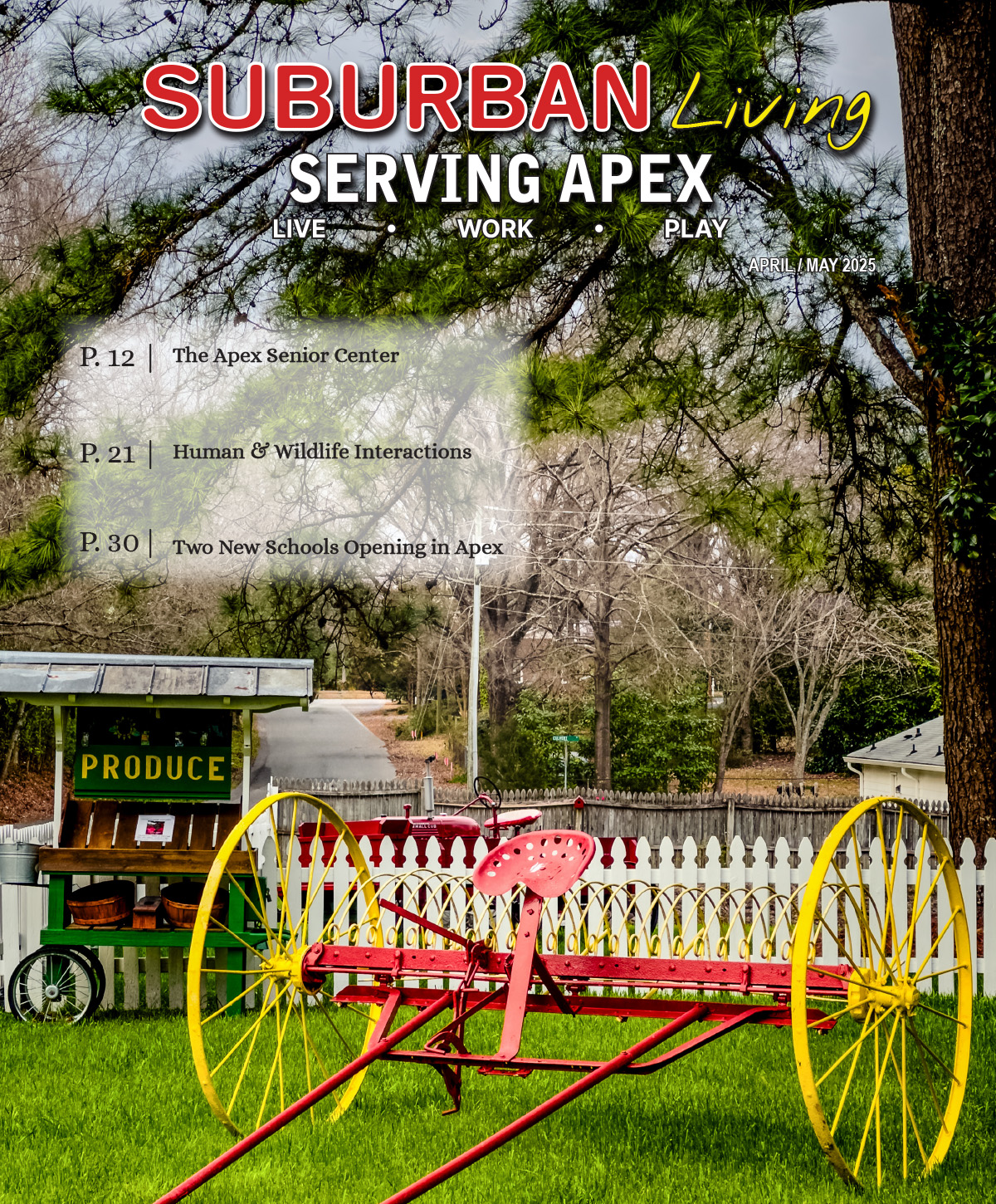

When passenger service was discontinued in 1969, the depot was acquired by the Town of Apex for use as a public library, although CSX Transportation Corporation retains ownership of the land. In 1988, the building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Today the historic Apex Union Depot welcomes thousands of visitors each year, serves as a meeting and information center, and plays host to a variety of events including band concerts and festivals. For many years, the depot was the site of the Apex Farmers Market on Saturdays during the summer months.

The Apex Union Depot is currently in service as the headquarters for the town’s Economic Development Department and the Apex Chamber of Commerce.