In her downtown Apex studio, artist Cathy Martin is surrounded by friendly faces, even when she’s alone. The faces are the portraits she has painted of victims of opioid overdose. She knows their names, but she has never met them nor in most cases has she ever met their families. Every face is someone’s son or daughter, their smiles and spirits preserved in brushstrokes on canvas, and as part of her mission, Cathy lovingly packages each painting and sends it as a gift to that child’s family.

The portraits are somber statements about the tragic consequences of opioid abuse, and a topic Cathy feels should be freely talked about, not hidden in shame. For her, the connection to drug addiction is a personal one. Her son, Alex, died in an automobile accident in 2003 when he was 25, leaving behind a one-year-old son who is now being raised by Cathy and her husband. While his death was not a direct result of drug use, Cathy says, “Drugs greatly influenced his life.”

Cathy started painting when she was a child and in her early career she taught art in both public and private schools. After staying home to raise her two sons, they started lives of their own and she decided it was time to paint full-time. A show she had in her hometown of Wilmington sold out. “I was happy,” Cathy says, “but I wasn’t fulfilled.”

“After our son died, I needed to have things going on around me so we found a house in downtown Apex and restored it. I opened a studio above [La Rancherita], the Mexican restaurant, and taught about six classes a week.” Eventually, Cathy moved into the space on the corner of N. Salem and Saunders Street.

Heartfelt Gifts for Hurting Families

For nearly a decade, Cathy wondered if there was something she could do to bring attention to the problem of drug abuse and eliminate the stigma associated with it. “I kept seeing young people’s obituaries in the newspaper and thought ‘What in the world is going on?’ I started painting the child [from their obituary photo] if it stated that opioids or heroin was the cause of death.”

That was two years ago. With their families’ permission, Cathy entered those first few portraits in art shows in Wilmington, North Carolina, and in Lake City, South Carolina. The South Carolina show, called Art Fields, drew 10,000 visitors, but the portraits were not for sale. Cathy gave them to the children’s families. It wasn’t long before her name was circulating on internet forums frequented by families of children who had died from heroin or opioids. Word spread and she received a call from a woman representing FED UP!, a national coalition started in 2012 to press the Federal Drug Administration to re-classify opioid drugs, stop the approval of other new opioids, and promote affordable treatment and recovery for addicts.

“With their parents’ knowledge, she started sending me pictures of children who had died. I started painting them and sending them back to the families. I’ve painted more than 100 children. They send me two or three photographs and I paint from those. It’s so strange; after I paint these children, I feel like I know them and I say to them, ‘Why couldn’t we help you?’ In every one, I have my son in mind.”

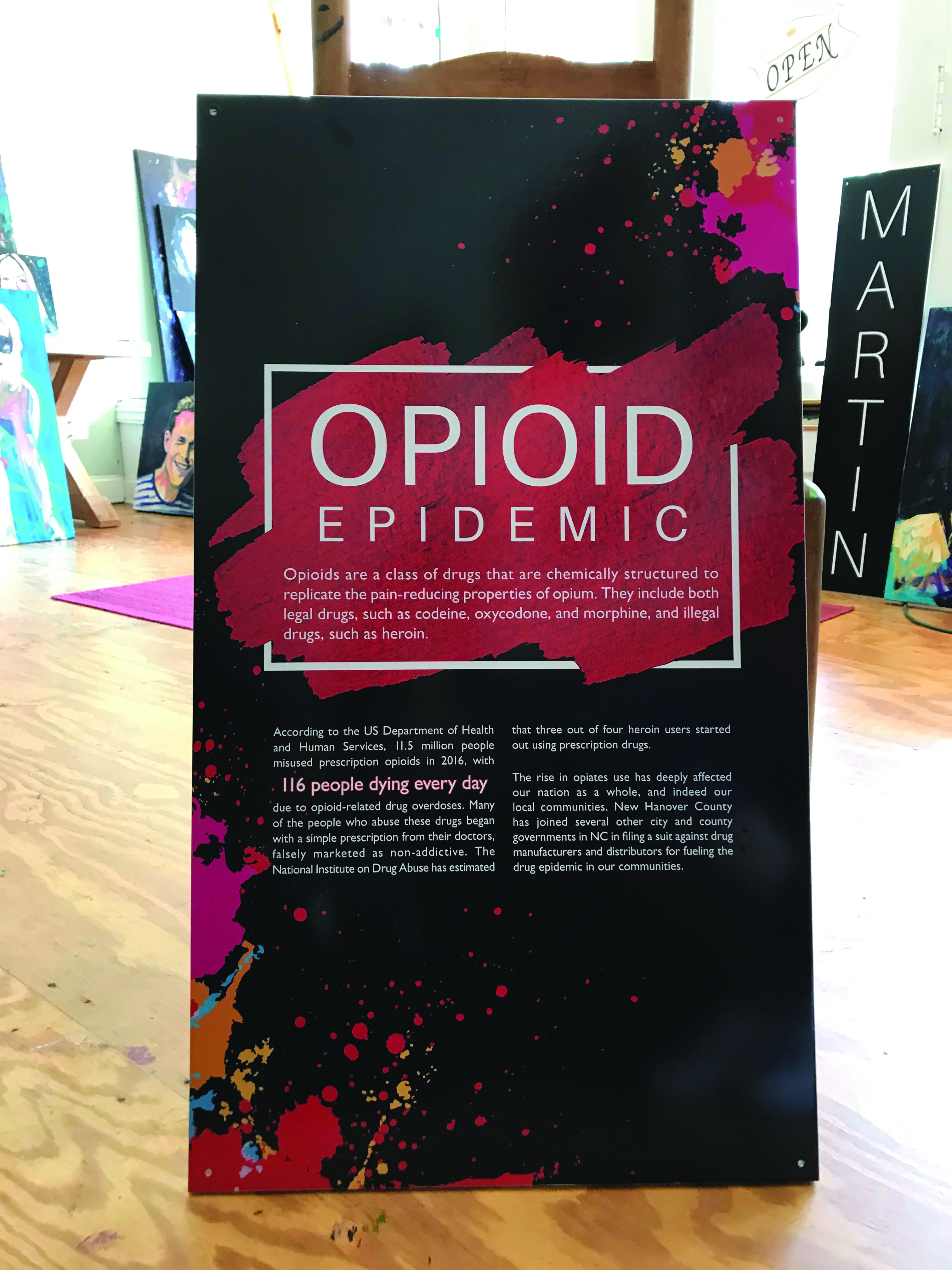

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “116 people die every day from opioid-related drug overdoses.” And rising statistics show that many heroin users and overdose victims first got addicted when taking painkillers prescribed by their physicians. Cathy feels strongly that prescribers need to be held accountable. “When these children couldn’t get any more, they went to heroin. Once they got addicted to an opioid, they didn’t have a choice. One pill can kill.”

A Problem Worth Talking About

While Cathy has never sought publicity for her portraits, she won’t shy away from an opportunity to bring awareness to the opioid epidemic and get people talking.

“I’ve always been vocal about the fact that my son’s connection to his lifestyle is why he died. My mission is to bring awareness to the issue of drug abuse and to take away the stigma. And there is a stigma. People treat you differently when you have a child that died of drug abuse. They want to blame the parents. They say it’s poor parenting. It’s hard enough when you lose a child and it’s even harder to then be judged by other people. I loved Alex and did the best I could. I still blame myself every single day and wonder what I could have done differently…and there’s a list.”

“But parents don’t need to be judged by other parents, because they can wake up one morning and it can be their child. These children are athletes, straight-A students, college graduates. They were the perfect children. Parents do not talk about drug abuse with their children. They think it won’t happen to them, that it’ll happen to other people’s children. It can be anybody’s child!”

“On occasion, I meet someone and when I tell them about my son, they open up about their own child. But if I hadn’t been honest, they would not have felt comfortable talking about it. When people hide things, it makes it harder for others. Thank goodness people are not hiding this issue as much. Now that people are being open about the opioid epidemic, it’s shattering that stigma.”

Cathy is supporting the FED UP! rallies in Raleigh and in Washington D.C by providing some of her portraits, but she is not planning any future shows. “The shows are to change the perception and make people aware of the problem, but all I want to do is paint these children. This is the most fulfilling thing I have ever done. I get beautiful notes from the parents. Some have said, ‘You got the outer child and you got the inner child, too.’ One parent wrote, ‘You gave me a second chance to hold my child.’ And that’s worth everything.”

A Call to Action

She may not have any art shows on the calendar, but there is one place where Cathy says she would gladly take her collection: Schools. “I would love to take a show into schools, talk to kids, and have someone with me who is knowledgeable about the facts. They could physically see the portraits and know that they cannot put this stuff into their mouths. The youngest children I painted were 13 years old. I’ve even had a few families where both children died. We need to get into the schools and I would love to get some help in doing this—I would love to challenge other artists to do this.”

Every day, Cathy receives new requests from grieving families to paint their children. That’s a sad realization. “They’re all so different and they’re all so loved,” she says. “It’s time to be honest, be open, and it will help someone else.”

For more information about the class of drugs called opioids and the abuse of prescription, synthetic, and illegal opioids, visit the National Institute on Drug Abuse (www.drugabuse.gov) and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS.gov). To find out how you can help end the opioid epidemic, visit the FED UP! Coalition’s website at feduprally.org.